Summary

Stark racial disparities in maternal and infant health in the U.S. have persisted for decades despite continued advancements in medical care. The disparate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic for people of color has brought a new focus to health disparities, including the longstanding inequities in maternal and infant health. Additionally, with Roe v. Wade now overturned, increased barriers to abortion for people of color may widen the already existing large disparities in maternal and infant health. Recently, there has been increased attention and focus on improving maternal and infant health and reducing disparities in these areas, including a range of efforts at the federal level. This brief provides an overview of racial disparities for selected measures of maternal and infant health, discusses the factors that drive these disparities, and provides an overview of recent efforts to address them. It finds:

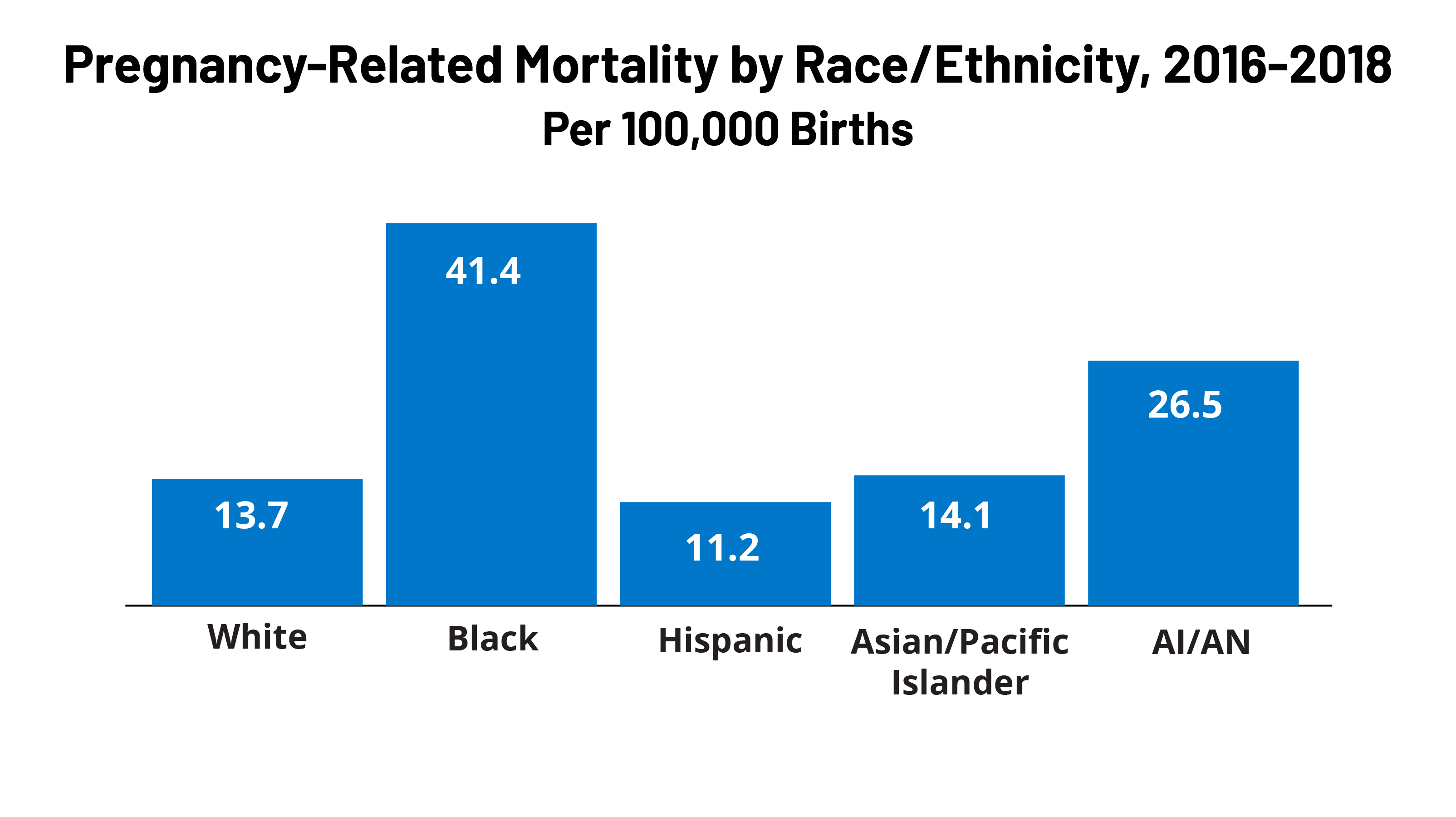

Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women have higher rates of pregnancy-related death compared to White women. Pregnancy-related mortality rates among Black and AIAN women are over three and two times higher, respectively, compared to the rate for White women (41.4 and 26.2 vs. 13.7 per 100,000). Black, AIAN, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) women also have higher shares preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women. Infants born to Black, AIAN, and NHOPI people have markedly higher mortality rates than those born to White women. Maternal death rates increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and racial disparities widened for Black women.

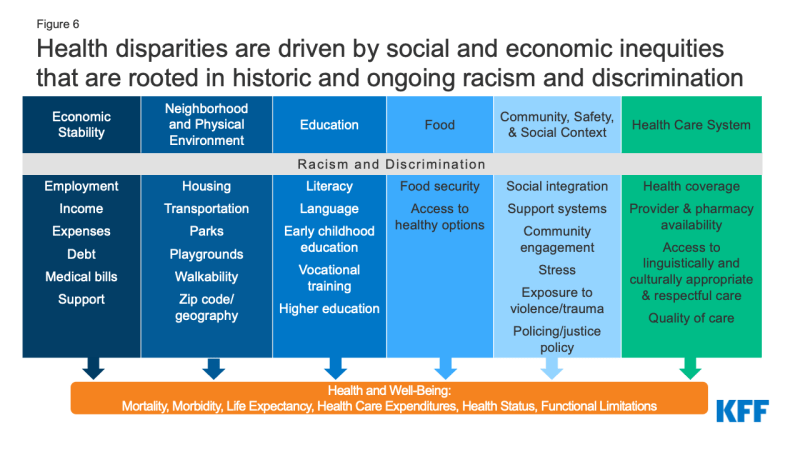

Maternal and infant health disparities are symptoms of broader underlying social and economic inequities that are rooted in racism and discrimination. Differences in health insurance coverage and access to care play a role in driving worse maternal and infant health outcomes for people of color. However, inequities in broader social and economic factors and structural and systemic racism and discrimination are primary drivers for maternal and infant health. Notably, disparities in maternal and infant health persist even when controlling for certain underlying social and economic factors, such as education and income, pointing to the roles racism and discrimination play in driving disparities.

The increased awareness and attention to maternal and infant health have contributed to a rise in efforts and resources focused on improving health outcomes in these areas and reducing disparities. These include efforts to expand access to coverage and care, increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversity the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting. However, addressing social and economic factors that contribute to poorer health outcomes and disparities will also be important. Moreover, the persistence of disparities in maternal health across income and education levels, points to the importance of addressing the roles of racism and discrimination within the health care system as part of efforts to improve health and advance equity.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated longstanding disparities in health and health care for people of color, including stark disparities in maternal and infant health. Despite continued advancements in medical care, rates of maternal mortality and morbidity and pre-term birth have been rising in the U.S. Maternal and infant mortality rates in the U.S. are far higher than those in similarly large and wealthy countries, and people of color are at increased risk for poor maternal and infant health outcomes compared to their White peers. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, maternal deaths have continued to rise and racial disparities have further widened. Moreover, with the overturning of Roe v. Wade, increased barriers to abortion for people of color may widen the already existing large disparities in maternal and infant health. Together these factors have contributed to growing attention and efforts to improve overall maternal and infant health and reduce disparities in these areas.

This issue brief provides analysis of racial and ethnic disparities across selected measures of maternal and infant health, discusses the factors that drive these disparities, and provides an overview of recent efforts to address them. It is based on KFF analysis of publicly available data from CDC WONDER online database, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics Reports, CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, and a report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO). While this brief focuses on racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and infant health, wide disparities also exist across other dimensions; for example, there is significant variation in some of these measures across states and disparities within rural communities.

Status of Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

Pregnancy-Related Mortality Rates

Approximately 700 women die in the U.S. each year as a result of pregnancy or its complications. Pregnancy-related deaths are deaths that occur within one year of pregnancy. Approximately one third (31{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}) occur during pregnancy, another third (36{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}) occur during labor or within the first week postpartum, and the remaining third (33{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}) occur one week to one year postpartum, underscoring the importance of access to health care beyond the period of pregnancy. Recent data has found that more than eight out of ten (84{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}) pregnancy-related deaths are preventable. Although leading causes of pregnancy-related death vary by race and ethnicity, cardiovascular conditions are the leading cause of pregnancy-related death among women overall, highlighting the importance of care for chronic conditions on pregnancy-related outcomes. More recent data from detailed maternal mortality reviews in 36 states found mental health conditions to be the overall leading cause of pregnancy related deaths.

Black and AIAN women have pregnancy-related mortality rates that are about three and two times higher, respectively, compared to the rate for White women (41.4 and 26.5 vs. 13.7 per 100,000 live births) (Figure 1). These disparities increase by maternal age. For example, the pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black women between ages 30 to 34 widens to over four times higher than the rate for White women (48.6 vs. 11.3 per 100,000), while the rate for AIAN women in the same age group is nearly four times as high as the rate for White women (41.2 per 100,000). Moreover, they persist across education levels. Notably, the pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black women who completed college education or higher is 5.2 times higher than the rate for White women with the same educational attainment and 1.6 times higher than the rate for White women with less than a high school diploma. There are small differences in the rate pregnancy-related death between Asian and Pacific Islander and White women (14.1 vs. 13.7 per 100,000), and the rate for Hispanic women is lower compared to that of White women (11.2 vs. 13.7 per 100,000). These findings may mask underlying differences in subgroups of these populations. Other research also shows that Black women are at significantly higher risk for severe maternal morbidity, such as preeclampsia, which is significantly more common than maternal death. Further, Black women have higher rates of admission to the intensive care unit during delivery compared to White women, which is considered a marker for severe maternal morbidity.

Maternal death rates increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and racial disparities widened for Black women. According to recent GAO analysis that examined maternal deaths during pregnancy or within 42 days of pregnancy, Black women had the highest maternal mortality rates across racial and ethnic groups during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 and also experienced the largest increase when compared to the year before the pandemic in 2019 (Figure 2). The maternal mortality rate for Hispanic women was less than the rate for White women prior to the pandemic but increased significantly and was similar to the rate for White women in 2020 and 2021. Data show that most of the increase in maternal deaths in 2020 and all of the increase in 2021 can be attributed to COVID-19 related deaths, which were higher among Black and Hispanic women (13.2 and 8.9 per 100,000, respectively) compared to White women (4.5 per 100,000).

Birth Risks and Outcomes

Black, AIAN, and NHOPI women are more likely than White women to have certain birth risk factors that contribute to infant mortality and can have long-term consequences for the physical and cognitive health of children. Preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks gestation) and low birthweight (defined as a baby born less than 5.5 pounds) are some of the leading causes for infant mortality. Receiving pregnancy-related care late in a pregnancy (defined as starting in the third trimester) or not receiving any pregnancy-related care at all can also increase risk of pregnancy complications. Black, AIAN, and NHOPI women have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women (Figure 3). Notably, NHOPI women are four times more likely than White women to begin receiving prenatal care in the third trimester or to receive no prenatal care at all (19{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809} vs. 5{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}). Black women also are nearly twice as likely compared to White women to have a birth with late or no prenatal care compared to White women (9{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809} vs. 5{cfdf3f5372635aeb15fd3e2aecc7cb5d7150695e02bd72e0a44f1581164ad809}).

While teen birth rates overall have declined over time, they are higher among Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI teens compared to their White counterparts (Figure 4). In contrast, the birth rate among Asian teens is lower than the rate for White teens. Many teen pregnancies are unplanned, and pregnant teens may be less likely to receive early and regular prenatal care. Teen pregnancy also is associated with increased risk of complications during pregnancy and delivery, including preterm birth. Teen pregnancy and childbirth can also have social and economic impacts on teen parents and their children, including disrupting educational completion for the parents and lower school achievement for the children. The drivers of teen pregnancy are multi-faceted and include poverty, history of adverse childhood events, and access to comprehensive education and health care services. Research studies have found that increased use of contraception as well as support for comprehensive sex education have helped lower the rate of teen births nationally.

Reflecting these increased risk factors, infants born to women of color are at higher risk for mortality compared to those born to White women. Infant mortality is defined as the death of an infant within the first year of life, but most cases occur within the first month after birth. The primary causes of infant mortality are birth defects, preterm birth and low birthweight, maternal pregnancy complications, sudden infant death syndrome, and injuries. Infants born to Black women are over twice as likely to die relative to those born to White women (10.4 vs. 4.4 per 1,000), and the mortality rate for infants born to AIAN and NHOPI women (7.7 and 7.2 per 1,000) is nearly twice as high (Figure 5). The mortality rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers is similar to the rate for those born to White women (4.7 vs. 4.4 per 1,000), while infants born to Asian women have a lower mortality rate (3.1 per 1,000). Data also show that fetal death or stillbirths—that is, pregnancy loss after 20-week gestation—are more common among Black women compared to White and Hispanic women. Moreover, causes of stillbirth vary by race and ethnicity, with higher rates of stillbirth attributed to diabetes and maternal complications among Black women compared to White women.

Factors Driving Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

The factors driving disparities in maternal and infant health are complex and multifactorial. They include differences in health insurance coverage and access to care. However, broader social and economic factors and structural and systemic racism and discrimination, also play a major role (Figure 6). In maternal and infant health specifically, the intersection of race, gender, poverty, and other social factors shapes individuals’ experiences and outcomes. Recently there has been broader recognition of the principles of reproductive justice, which emphasize the role that the social determinants of health and other factors play in reproductive health for communities of color. Notably, Hispanic women and infants fare similarly to their White counterparts on many measures of maternal and infant health despite experiencing increased access barriers and social and economic challenges typically associated with poorer health outcomes. Research suggests that this finding, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic or Latino health paradox, in part, stems from variation in outcomes among subgroups of Hispanic people by origin, nativity, and race, with better outcomes for some groups, particularly recent immigrants to the U.S. However, the findings still are not fully understood.

Figure 6: Health disparities are driven by social and economic inequities that are rooted in historic and ongoing racism and discrimination

Disparities in maternal and infant health, in part, reflect increased barriers to care for people of color. Research shows that coverage before, during, and after pregnancy facilitates access to care that supports healthy pregnancies, as well as positive maternal and infant outcomes after childbirth. Overall, people of color are more likely to be uninsured and face other barriers to care. Medicaid helps to fill these coverage gaps during pregnancy and for children. However, women of color are at increased risk of being uninsured prior to their pregnancy and, historically, many have lost coverage at the end of the 60-day Medicaid postpartum coverage period due to lower eligibility levels for parents compared to pregnant women, particularly in states that have not implemented the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion. Beyond health coverage, people of color face other increased barriers to care, including limited access to providers and hospitals and lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care. These challenges may be particularly pronounced in rural and medically underserved areas. For example, research suggests that a rise in closures of hospitals and obstetric units in rural areas has a disproportionate impact in communities with larger shares of Black patients.

Research also highlights the role of racism and discrimination plays in driving racial disparities in maternal and infant health. Research has documented that social and economic factors, racism, and chronic stress contribute to poor maternal and infant health outcomes, including higher rates of perinatal depression and preterm birth among African American women and higher rates of mortality among Black infants. In recent years, research and news reports have raised attention to the effects of provider discrimination during pregnancy and delivery. News reporting and maternal mortality case reviews have called attention to a number of maternal deaths and near misses among women of color where providers did not or were slow to listen to patients. In one study, Indigenous, Hispanic, and Black women reported significantly higher rates of mistreatment (such as shouting and scolding, ignoring or refusing requests for help) during the course of their pregnancy. Even controlling for insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions, people of color are less likely to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of care. One recent study of hospital births in Florida found that there were significant improvements in mortality for Black newborns who were cared for by Black physicians, pointing to the importance of culturally concordant or competent care. A KFF/The Undefeated survey found that most Black adults believe the health care system treats people unfairly based on their race, and one in five Black and Hispanic adults report they were personally treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity while getting health care in the past year, with a higher share of Black mothers reporting unfair treatment. Black adults also were more likely than White adults to report feeling a provider didn’t believe they were telling the truth and being refused a test, treatment, or pain medication they thought they needed.

Current Efforts to Address Maternal and Infant Health Disparities

Increased awareness and attention to maternal and infant health have contributed to a rise in efforts and resources focused on improving health material and infant health outcomes and reducing disparities. These include efforts to expand access to coverage and care, increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversity the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting.

In June 2022, the Biden Administration released the Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis. The Blueprint outlines priorities and actions across federal agencies to improve access to coverage and care, expand and enhance data collection and research, grow, and diversify the perinatal workforce, strengthen social and economic support, and increase trainings and incentives to support women being active participants in their care before, during and after pregnancy. Several of these proposals are included in the MOMNIBUS, a federal legislative package sponsored by the Congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus. Federal agencies also have announced plans and actions to support the Blueprint, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which released a maternity care action plan in July 2022; the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which has committed $350 million to states to strengthen maternal and child health, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), which invested $8.5 million in initiatives designed to reduce pregnancy-related deaths and complications that disproportionately impact people of color and those living in rural areas.

Recent federal legislation has expanded access to and helped stabilize Medicaid coverage during the postpartum period. Medicaid covers almost half of births nationally. However, historically, many pregnant women lost coverage at the end of a 60-day postpartum coverage period because eligibility levels are lower for parents than pregnant women in many states, particularly those that have not implemented the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 provided states a new option for five years, beginning April 1, 2022, to extend postpartum coverage to a full year. As of October 27, 2022, 27 states, including DC, had implemented a 12-month postpartum coverage extension, and an additional seven states were planning to implement the extension. KFF analysis suggests that the coverage extension could prevent hundreds of thousands of enrollees from losing coverage in the months after delivery. In addition, at the start of the pandemic, Congress enacted the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), which included a requirement that Medicaid programs keep people continuously enrolled through the end of the month in which the COVID-19 PHE ends in exchange for enhanced federal funding. This provision has prevented coverage gaps or losses that otherwise might have occurred during the postpartum period due to changes in eligibility and/or administrative challenges associated with maintaining coverage. However, coverage losses may occur after states resume redeterminations of eligibility when the PHE ends. Additional actions may also help to reduce disparities, including adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion in the 12 remaining states that have not yet expanded, as nearly six in ten adults in the coverage gap in these states are adults of color. Further, Medicaid expansion promotes continuity of coverage in the prenatal and postpartum periods. The Biden Administration Blueprint encourages states to take-up the ARPA postpartum coverage option and urges Congress to close the Medicaid coverage gap and require all states to provide 12 months postpartum Medicaid and CHIP coverage.

Implementation of evidence-based best practices may help to improve maternal and infant health outcomes. As part of its maternity care action plan, CMS has outlined a proposal for a “Birthing-Friendly” hospital designation that would provide public information on hospitals that have implemented best practices in areas of health care quality, safety, and equity for pregnant and postpartum patients. Moreover, in 2022, CMS has launched a new effort within its maternal and infant health initiative to reduce low-risk Cesarean births to improve infant and maternal health. This program is centered around a learning collaborative that outlines approaches Medicaid and CHIP agencies can put in place to reduce low-risk cesarean deliveries and works directly with states to implement evidence-based best practices in their state.

Recent actions have enhanced access to data on maternal and infant health outcomes and disparities. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts national pregnancy-related mortality surveillance and regularly releases findings as a source of information around the risk factors and causes of pregnancy-related deaths. The CDC also developed Levels of Care Assessment Tool (LOCATe) to assist states by standardizing their assessments of levels of maternal and neonatal care and promotes the Hear Her campaign to raise awareness of urgent maternal warning signs during and after pregnancy. In addition, the CDC supports state efforts to prevent maternal deaths through several efforts including the Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality (ERASE MM) program and perinatal quality collaboratives (PQCs), which aide in increasing understanding of the drivers of pregnancy related mortality and identify health care processes that contribute to improved outcomes for mothers and infants to reduce racial disparities and geographic disparities. Maternal mortality review committees in several states are comprised of clinicians, community members, researchers, and other experts to review all deaths within one year of pregnancy, and identify causes, drivers, and opportunities for quality improvement. Data collection by these committees has been particularly important in understanding that a large share of deaths are preventable as well as identifying the significant portion of deaths that occur after delivery and encouraging efforts to strengthen care in the postpartum period. Moreover, there are several research and data collection initiatives directed by CDC to monitor sudden unexpected infant deaths, reduce infant mortality and build epidemiological support at the state and local level to improve maternal and child health programs.

A variety of efforts are underway to increase workforce diversity and expand access to doula and other services to improve maternal and infant health outcomes and reduce disparities. Studies have shown that a more diverse healthcare workforce and the use of doulas may improve birth outcomes. The percent of maternal health physicians and registered nurses that are Hispanic or Black is lower than their share of the female population of childbearing age. The Biden Administration’s Blueprint includes efforts by HRSA to develop a maternal care pipeline to provide scholarships to students from underrepresented communities in health professions and nursing schools to grow and diversify the maternal care workforce. The use of doula services is another approach to increase diversity and expand the maternal health workforce. Doulas are trained non-clinicians who assist a pregnant person before, during and/or after childbirth by providing physical assistance, labor coaching, emotional support, and postpartum care. Pregnant women who receive doula support have been found to have shorter labors and lower C-sections rates, fewer birth complications, are more likely to initiate breastfeeding, and their infants are less likely to have low birth weights. The Biden Administration’s Blueprint includes a FY2023 budget request for $20 million to grow and diversify the doula workforce. Additionally, in recent years there has been growing interest in expanding coverage of doula services through Medicaid. Federal legislation has been introduced to expand coverage of doula services through Medicaid, and some states are taking steps to include coverage through their state programs. State efforts to date have had mixed success, in part because of challenges with certification requirements and low reimbursement levels. In 2022, there were at least 17 states considering, planning, or implementing coverage of doula services through Medicaid reimbursements. Some states are also implementing or expanding coverage for other services focused on improving maternal and infant health including home visiting programs to teach positive parenting and other skills; postpartum services provided by lactation counselor and consultants, public health nurses, and medical caseworkers; as well as targeted case management and other programs to meet needs of pregnant and postpartum individuals with substance use disorders.

States, providers and health systems, foundations, and communities also are engaged in a broad range of efforts to advance maternal and child health and reduce disparities. Several states have developed plans and initiatives to address disparities in maternal and infant outcomes. For example, New Jersey launched the Nurture NJ Strategic Plan to outline challenges, action areas, and recommendation to achieve equity for all women with a focus on dismantling structural racism and addressing social determinants of health. In addition, many state Medicaid programs have implemented policies, programs, and initiatives to improve maternity care and outcomes and , including expanding eligibility for people during and after pregnancy, conducting outreach and education to enrollees and providers, expanding coverage for benefits such as doula care, home visits, and substance use disorder and mental health treatment, and using new payment, delivery, and performance measurement approaches. Also, five states reported including Performance Improvement Projects (PIPS) for their Medicaid services that focused specifically on reducing disparities related to maternal and child health in Fiscal Year 2022, including Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, and Texas. California is in the process of implementing provisions from legislation passed in recent years requiring implicit bias training for all perinatal health workers, as well as elements of the California MOMNIBUS, which directs the state to invest in improved data analysis, streamlining administrative procedures within the welfare program for pregnant people, and broadening the midwifery workforce. Northwell Health, the largest healthcare provider in New York, recently launched a Center for Maternal Health to address pregnancy related health risks facing Black women by seeking to address issues within healthcare and in the community that arise before, during, and after pregnancy. The Changing Woman Initiative is a Native American midwifery organization in New Mexico providing culturally centered care to address maternal health disparities, high rates of gestational diabetes, and low birth weight deliveries among Indigenous women.

A range of organizations are advocating for more interventions and supports to address maternal mental health and substance use issues, major causes of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity. The field of maternal mental health and substance use encompasses a large range of conditions that affect the health of parents and their infants. Some studies have found higher rates of postpartum depression among some pregnant and postpartum women of color, but many mental health conditions are undiagnosed and untreated due to stigma and poor access to treatment. These issues also limit access to services for pregnant and postpartum people suffering from substance use disorders. Community-based and provider organizations are calling for a number of policy and structural changes to address these large challenges, including broader insurance coverage for behavioral health care, higher reimbursement for existing treatment services, greater education and awareness about screening for mental health and substance use conditions among health care providers and childbearing people. Federal initiatives in this area include CMS’ Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model, a grant program for states to better integrate care for mothers and infants exposed to opioids, and state-level learning communities on mental health, supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) .

At the same time many efforts are focused on improving maternal and infant health and reducing disparities, the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade may contribute to widening disparities in maternal and infant health, People of color are likely to be disproportionately affected by state actions to fully prohibit or implement extensive restrictions on abortions as they are more likely to seek abortions and more likely to face structural barriers that will make it more difficult to travel out of state for an abortion, including more limited access to health care and fewer financial and transportation resources. Increased barriers to abortion for people of color may widen the already existing large disparities in maternal and infant health, have negative economic consequences for families, and increase risk of criminalization for pregnant people of color.

Looking Ahead

Overall, these data show that racial disparities in maternal and infant health persist. Improving maternal and infant health is key for preventing unnecessary illness and death and advancing overall population health. Healthy People 2030, which provides 10-year national health objectives, identifies the prevention of pregnancy complications and maternal deaths and improvement of women’s health before, during, and after pregnancy as a public health goal. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlights the urgency and importance of addressing disparities in health more broadly and increased attention to disparities in maternal and infant health specifically. Moreover, the overturning of Roe v. Wade may contribute to worsening disparities in maternal and infant health, further amplifying the importance of attention to these areas.

The increased awareness and attention to maternal and infant health have contributed to a rise in efforts and resources focused on improving health outcomes in these areas and reducing disparities. These include efforts to expand access to coverage and care, increase access to a broader array of services and providers that support maternal and infant health, diversity the health care workforce, and enhance data collection and reporting. However, addressing social and economic factors that contribute to poorer health outcomes and disparities will also be important. Moreover, the persistence of disparities in maternal health across income and education levels, points to the importance of addressing the roles of racism and discrimination within and beyond the health care system as part of efforts to improve health and advance equity.

More Stories

Heart-healthy habits linked to longer life without chronic conditions

Hoda Kotb Returns To TODAY Show After Handling Daughter’s Health Matter

Exercise 1.5 times more effective than drugs for depression, anxiety